The Road to St. John

by Erin B. Hills

When Wilford Woodruff was a young missionary, he would spend time during his personal and companionship worship singing hymns. For example, on one occasion while serving in the Fox Islands of Maine, he and his companion, Jonathan Hale, retired to a grove of trees at the end of the day and sang “The Sun That Declines in the Far Western Sky,”1 a hymn, Wilford noted, that was composed by Thomas B. Marsh and Orson Pratt.2 Though I had never heard of this particular hymn before, after I read about this experience, I became curious—what was Wilford Woodruff’s favorite hymn?

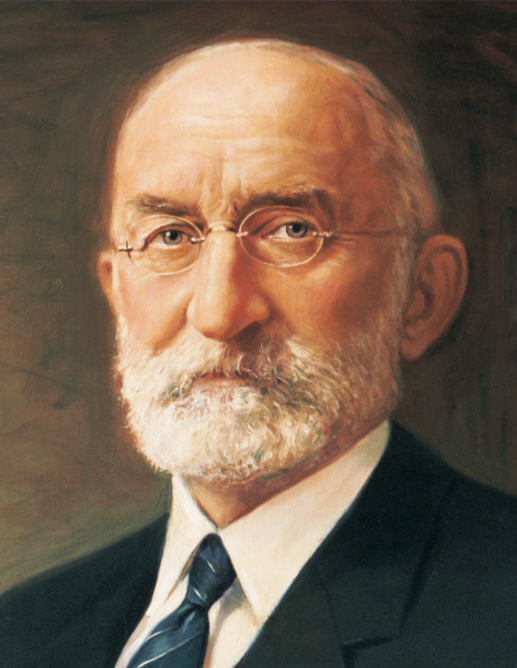

Thanks to a recollection of President Heber J. Grant in the April 1937 general conference, I learned the answer: “God Moves in a Mysterious Way.” President Grant said, “This was the favorite hymn of the late President Wilford Woodruff. He loved it. We sang it, I am sure, sometimes twice a month in our weekly meetings in the Temple, and very seldom did a month pass by when that song was not called for by Brother Woodruff. He believed in this work with all his heart and soul, and labored with all the power that God gave him for its advancement. That hymn is an inspiration.”3

Heber J. Grant

Heber J. Grant

The hymn was written by William Cowper, a British poet, and originally titled “Light Shining out of Darkness.” The message within the hymn is that although we cannot comprehend the ways of God, we must take courage—for though we will pass through difficult times, God is full of mercy and love, and sweet will be the final reward.

God moves in a mysterious way

His wonders to perform;

He plants his footsteps in the sea

And rides upon the storm.

Ye fearful Saints, fresh courage take;

The clouds ye so much dread

Are big with mercy and shall break

In blessings on your head.

His purposes will ripen fast,

Unfolding ev’ry hour;

The bud may have a bitter taste,

But sweet will be the flower.

Blind unbelief is sure to err

And scan his works in vain;

God is his own interpreter,

And he will make it plain.4

William Cowper

William Cowper

The words of this hymn flooded my mind recently as I read journal entries Wilford Woodruff penned in the summer of 1849. And I began to understand why this hymn was Wilford’s favorite. To give some background, in 1849, Wilford and his family were living in Cambridge, Massachusetts, while he presided over the Church in the eastern states. During the summer, Wilford had left his family to travel north and meet with the Saints in Maine and Canada. One of his first visits was to the Saints he had baptized nine years earlier on the Fox Islands of Maine.

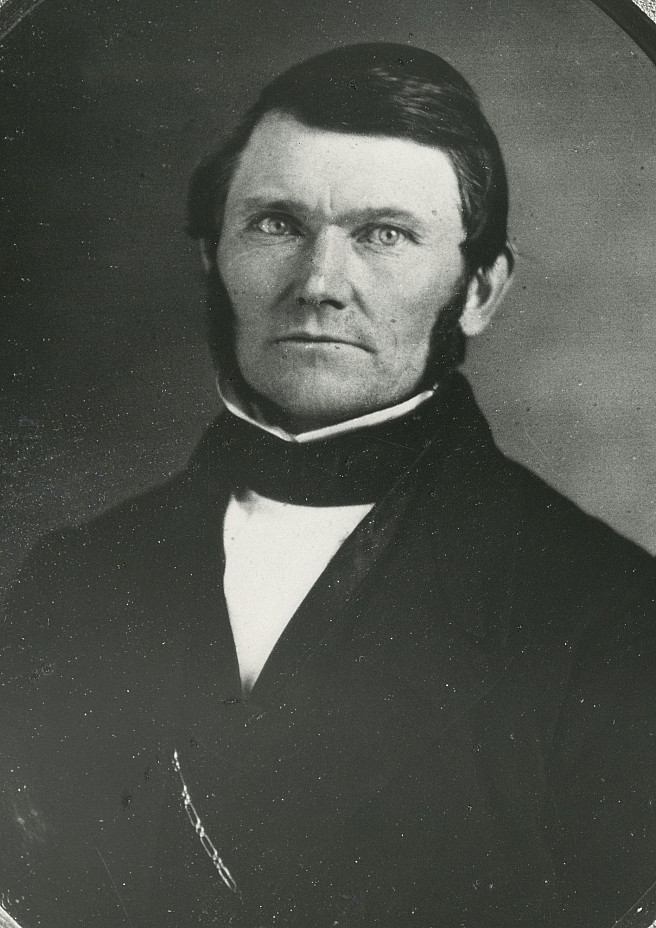

Wilford Woodruff March 8, 1849 Boston, MA

Wilford Woodruff March 8, 1849 Boston, MA

After he left the Fox Islands, he traveled to Thomaston, Maine, where he completed some missionary work and waited for passage to New Brunswick, Canada. For the next two weeks, his trip did not go as scheduled. Wilford took passage out of Thomaston on July 7, 1849, having planned a three-to-four days’ journey by sea to St. John, New Brunswick. He made it to “Musketoe Harbor” before the winds died and the fog rolled in. And with “no way to get out of the country only by water,” Wilford was stuck.5 In a letter written to his wife, Phebe, Wilford described his time in “Musketoe Harbor” as such: “One whole week to a day of my time has been spent in a dreary manner . . . bound fast by smoke, fog & calm with nothing to clear the heart or please the eye except to wander over the ragged rocks & forest, pick a few strawberries & wintergreens, see a few rough fisherman, catch a few lobsters & fish, & live, eat, drink, & sleep, in [the] forecastle of a small sloop.”6

.png) Journal Entry July 7, 1849

Journal Entry July 7, 1849

During this time, he felt homesick, and “lived mostly upon black tea, land sea bread & Molasses, fresh fish, & Lobsters.”7 He preached to the fishermen in the Harbor, but mostly he waited for the weather to clear so he could get on with his journey.8 Finally, late on July 13, the small ship Wilford was a passenger on sailed out of the harbor and headed toward New Brunswick. The ship was going only as far as Machias Port, and when Wilford arrived, he learned he couldn’t get passage to St. John for several days. Another setback was not what Wilford wanted. Luckily, he found a captain who was just leaving for Beaver Harbor, and who was willing to take Wilford along, bringing him sixty miles closer to his destination. He determined that once he was in Beaver Harbor, he would then take the stage to St. John.

Ten days had passed since Wilford had sailed out of Thomaston. It was just a day’s journey by stage from Beaver Harbor to St. John, and Wilford planned to be there the evening of July 16. But it was not to be. Wilford got up early that Monday morning and walked seven miles to the stage home. He waited three hours for the stage to arrive, and when it came, it was too loaded down and could not take him. He wrote, “Here I was 42 miles from St Johns on foot & no conveyance with A Heavy travelling bag with A vast burning forest to go through I did not stop to meditate or complain of my situation but swung my carpet bag over my shoulder again & started on my journey on foot, in good spirits.”9

Many of us would be discouraged in such a situation. Perhaps we would turn around and head back to Beaver Harbor and hope for a ship to take us to St. John. But Wilford felt compelled to continue his journey on foot.

After walking a couple miles, Wilford met up with an Irishman. The Irishman’s name and his reason for being on the same road as Wilford were not recorded in the journal entry. All Wilford wrote was that they “walked together several miles.”10 They eventually made it to a Mr. McGowen’s, which Wilford noted was the next “stage home” on the road.11 At this point Wilford had walked “about 20 miles.”12

And this is where I paused in my reading. I spent some time thinking about this journey that seemed to be going all wrong. And then the words “God Moves in a Mysterious Way” flooded my mind, and I began to ask questions: Who was the Irishman? What did he need that day? What if everything had moved according to plan and Wilford had made it to St. John a week sooner? And finally—what did Wilford and the Irishman talk about while they walked?

If you were on the Lord’s errand, as Wilford was, what would you share? I like to think that Wilford offered council or encouragement—that he shared his testimony of the restored gospel, or that he asked about the man’s life and family.

Wilford recorded that at one point, a man came along in a wagon and took his bag the last five miles to Mr. McGowen’s. Why didn’t the man offer Wilford a ride? Perhaps he did. Perhaps walking with the Irishman was more important to Wilford than getting a ride. Once the two men arrived at Mr. McGowen’s, they parted ways. Wilford wrote, “The Irishman left, I saw no more of him.”13 After eating some dinner at Mr. McGowen’s, Wilford walked another fifteen miles before he stopped for the night. He still had fifteen to go before he would reach St. John.

The trip from Thomaston to St. John took more than twice as long to complete than it should have. The final leg of Wilford’s journey was no exception. What should have taken a day, instead took two. Wilford was tired, his bag was heavy, his muscles were sore, yet he didn’t seem to question why the trip took such a turn. With fresh courage and good spirits, he continued his journey. It is clear to me as I read about Wilford Woodruff’s life that God’s purposes and wonders were performed through Wilford because he was willing to serve the Lord at all costs. I like to think that Wilford Woodruff’s walk with the Irishman was all according to God’s plan.

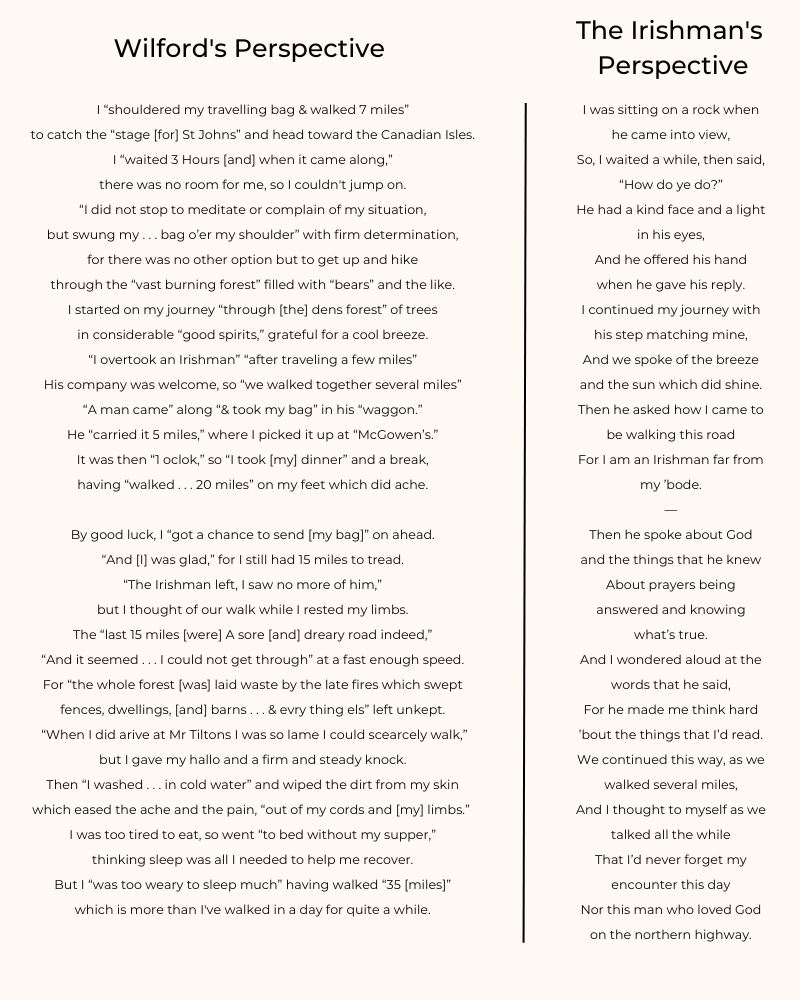

Feeling inspired by this story, I wrote a poem based on Wilford’s entry of July 16, 1849, and I tried to capture Wilford’s experience based on his words. I also wrote a companion poem from the Irishman’s point of view, as I imagine it.

The Wilford Woodruff Papers Foundation’s mission is to digitally preserve and publish Wilford Woodruff’s eyewitness account of the Restoration of the gospel of Jesus Christ from 1833 to 1898. It seeks to make Wilford Woodruff’s records universally accessible to inspire all people, especially the rising generation, to study and to increase their faith in Jesus Christ. See wilfordwoodruffpapers.org.

Erin B. Hills is a Senior Research Assistant with the Wilford Woodruff Papers Project and a graduate of Brigham Young University–Idaho. Erin loves learning about the life of Wilford Woodruff and happily shares all her favorite stories with her family and friends. She lives with her husband and five children in Virginia.

Some original text has been edited for clarity and readability.

-

“Collection of Sacred Hymns, 1835,” p. 37, The Joseph Smith Papers, josephsmithpapers.org/collection-of-sacred-hymns.

-

Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, August 31, 1837, p. 172, The Wilford Woodruff Papers, wilfordwoodruffpapers.org/journal/1837-08-31.

-

Heber J. Grant, conference reports of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, April 1937, p. 11, Church History Library, catalog.ChurchofJesusChrist.org/.

-

William Cowper, “Light Shining out of Darkness,” Poetry Foundation, poetryfoundation.org/light-shining-out-of-darkness.

-

Letter to Phebe Whittemore Carter Woodruff, July 14, 1849, p. 2, The Wilford Woodruff Papers, wilfordwoodruffpapers.org/letter/1849-07-14.

-

Letter to Phebe Whittemore Carter Woodruff, July 14, 1849, pp. 1–2, The Wilford Woodruff Papers, wilfordwoodruffpapers.org/letter/1849-07-14.

-

Letter to Phebe Whittemore Carter Woodruff, July 14, 1849, pp. 1–2, The Wilford Woodruff Papers, wilfordwoodruffpapers.org/letter/1849-07-14.

-

Letter to Phebe Whittemore Carter Woodruff, July 14, 1849, p. 2, The Wilford Woodruff Papers, wilfordwoodruffpapers.org/letter/1849-07-14.

-

Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, July 16, 1849, p. 221, The Wilford Woodruff Papers, wilfordwoodruffpapers.org/journal/1849-07-16.

-

Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, July 16, 1849, p. 221, The Wilford Woodruff Papers, wilfordwoodruffpapers.org/journal/1849-07-16.

-

Letter to Phebe Whittemore Carter Woodruff, July 24, 1849, p. 1, The Wilford Woodruff Papers, wilfordwoodruffpapers.org/letter/1849-07-24.

-

Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, July 16, 1849, p. 221, The Wilford Woodruff Papers, wilfordwoodruffpapers.org/journal/1849-07-16.

-

Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, July 16, 1849, p. 221, The Wilford Woodruff Papers, wilfordwoodruffpapers.org/journal/1849-07-16.